Intro

Since its introduction to the world, Apache Kafka has established itself as the de facto standard for distributed messaging, powering numerous organizations worldwide, with use cases ranging from microservices communication to real-time analytics.

Its architecture was designed in an era dominated by on-premise data centers, where servers were pre-purchased, and the network was not as fast as it is today. However, that design philosophy reveals significant friction when deployed in modern cloud environments, with skyrocketing cross-availability zone network costs, and it is challenging to scale compute and storage independently.

This reality is driving an industry-wide shift toward a new paradigm: diskless Kafka. In this article, we will first discuss the Kafka diskless trend and explore some available solutions on the market. We will then take a closer look at AutoMQ, one of the earliest companies to attempt to make Kafka diskless.

Disk and Diskless

Kafka was built over a decade ago by LinkedIn to provide an efficient way to decouple producers and consumers; both sides communicate with brokers to exchange messages. As discussed, Kafka was built at a time when:

- Leveraging a local data center is the main approach instead of cloud services.

- The network was not so fast; the standard way to build a system is to stick the compute and storage together.

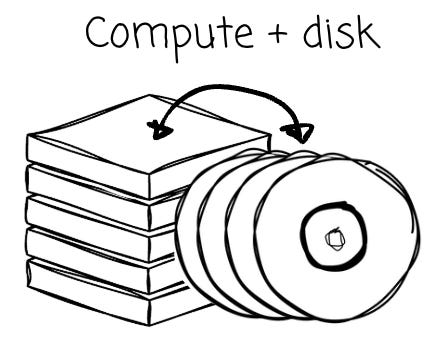

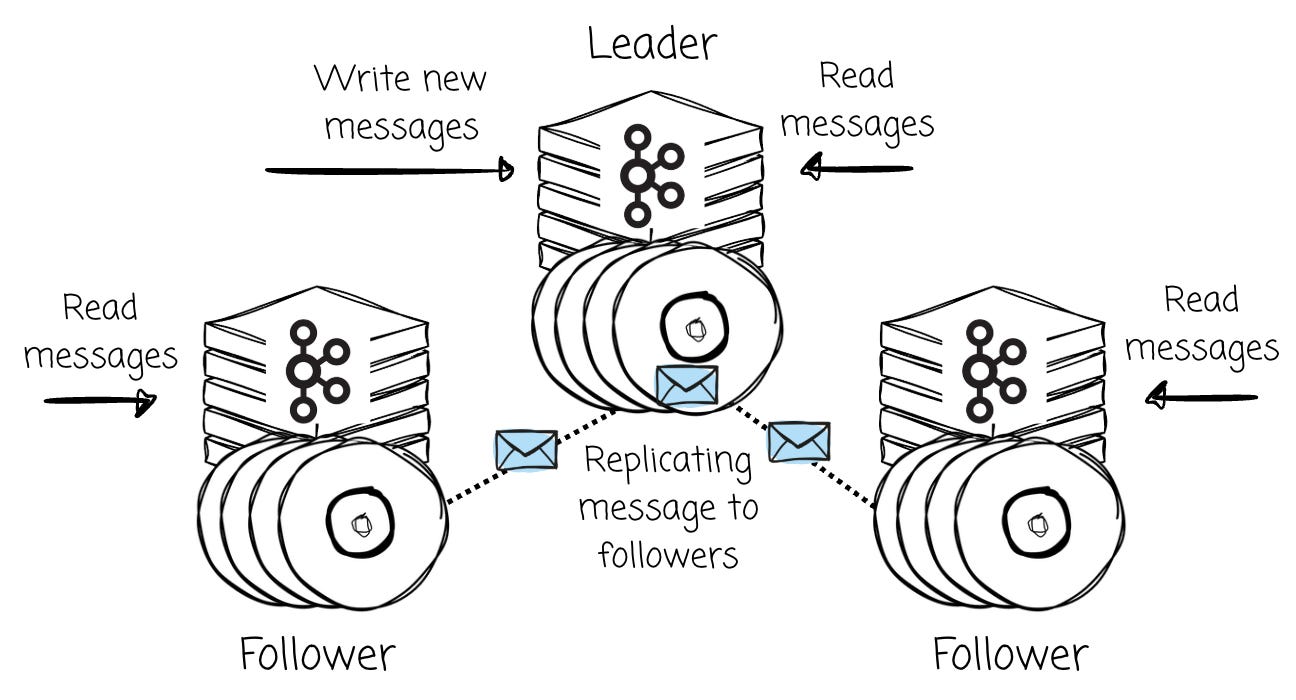

Adhering to these facts, Kafka’s brokers were designed to store messages directly on the local disk, and data redundancy and availability are achieved through message replication between brokers.

This means scaling storage requires adding more machines, forcing users to provision additional CPU and memory, even if the existing compute resources are underutilized.

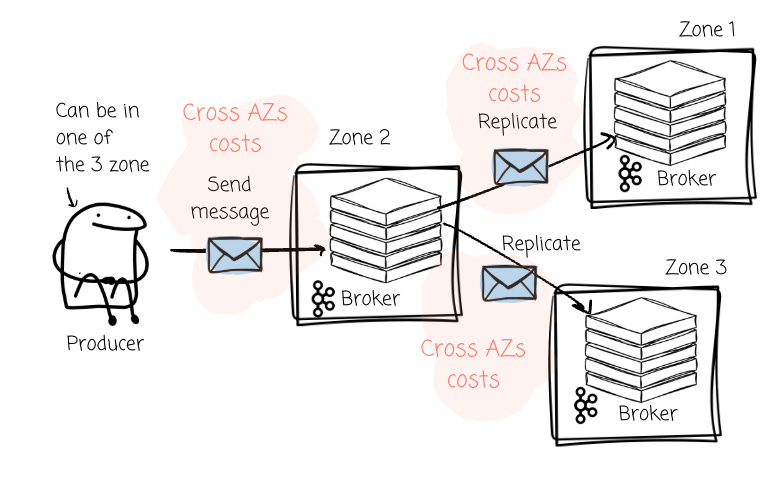

Beyond resource inefficiency, broker-level replication creates a significant and often overlooked financial drain in multi-Availability Zone (AZ) cloud deployments. This cost manifests in two ways:

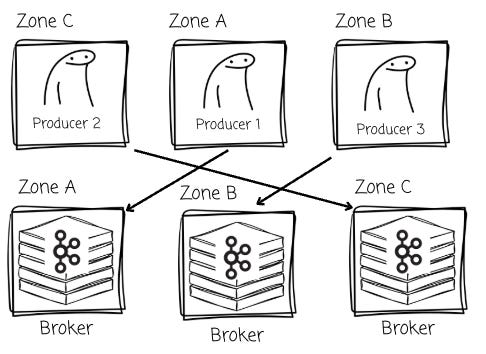

- Producer Traffic Costs: In a typical high-availability setup with brokers spread across three AZs, producers must send their messages to the leader broker for a given partition. If a Kafka cluster spans the leader partitions across three zones, producers will send messages to brokers that are located in different zones approximately two-thirds of the time.

- Replication Traffic Costs: After the leader receives the data, it must then replicate it to its follower brokers in the other two AZs to ensure durability. This process generates an even larger wave of cross-AZ data transfer, incurring a second set of network fees for the same message data.

Recognizing these challenges, various systems are emerging with a new approach.

Diskless

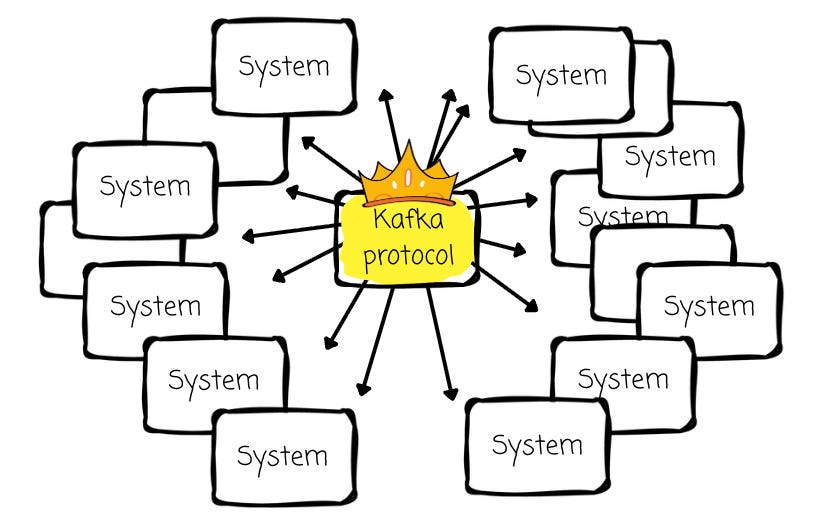

Although Kafka has weaknesses, its API has won. It’s the industry standard for data streaming, and a massive ecosystem has been built around it.

Therefore, if any vendors attempt to offer a better alternative, their solution must be compatible with Kafka. A completely new system is not a good idea; redesigning Kafka’s storage layer is a more effective approach.

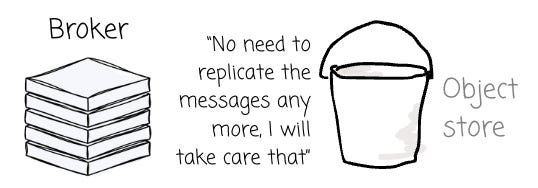

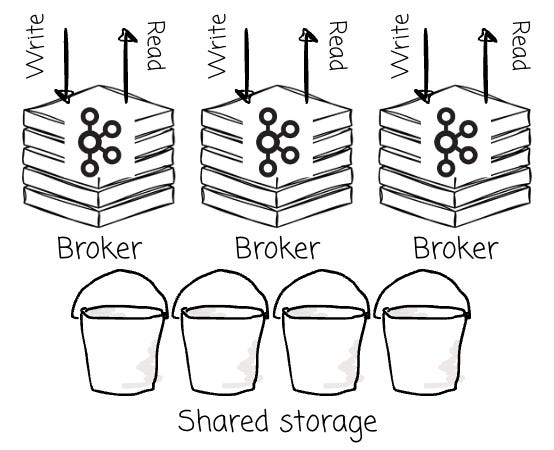

Diskless architecture is an approach where all messages are moved entirely from brokers and stored in object storage.

This new model fundamentally redefines how a Kafka-compatible system operates in the cloud. The benefits are immediate and transformative:

- Cost Efficiency: Object storage is an order of magnitude cheaper per gigabyte than the high-performance block storage required by traditional Kafka brokers

- Scaling: Broker nodes become stateless compute units that can be scaled up or down based on processing demand, while storage capacity scales independently and automatically within the object store.

- Durability and Availability: Cloud object storage services are designed for extreme durability (often 99.999999999% or higher) and automatically replicate data across multiple AZs. This reliability is fundamentally achieved using techniques like Erasure Coding (EC) alongside automatic data replication, which often spans multiple AZs. Because this robust data protection is handled by the storage layer itself, there is no need for costly and complex broker-level data replication, thus eliminating the associated cross-AZ traffic problem.

It is worth noting that the diskless architecture differs from the Kafka tiered architecture proposed in Kafka Tiered Storage (KIP-405). This proposal introduces a two-tiered storage system:

Local storage (broker’s local disk) stores the most recent data.

Remote storage (S3/GCS/HDFS) stores historical data.

However, brokers are not entirely stateless. All the challenges we discussed above are still present.

From WarpStream, BufStream, to Aiven, all of them offer Kafka alternative solutions based on this approach. The rapid proliferation of these platforms highlights the significance of the problem they aim to solve. While all share the common goal of leveraging object storage to reduce costs and improve elasticity, they are not created equal.

In this article, I will focus on AutoMQ, which offers a unique diskless option for Kafka compared to others.

AutoMQ

100% Kafka compatibility and Openness

As we discussed, the new system must adhere to the Kafka protocol.

The Kafka protocol is built around local disks. All operations are centered around this design, from appending messages to the physical logs to serving consumers by locating the offset in the segment files.

That said, developing a Kafka-compatible solution using object storage is a significant challenge. Putting performance aside, writing to object storage differs completely from how data is written to disk. We can’t open an immutable object and append data to the end, as we can with a filesystem.

Some (e.g., WarpStream, Bufstream) decided to create a new protocol that can do two things:

Operate with object storage

Provide Kafka compatibility

They believe this approach is more straightforward than leveraging the open-source Kafka protocol. This approach, however, presents some challenges. It is challenging to keep up with the community’s changes, which can often result in delays or the complete loss of certain Kafka API features. For instance, it took WarpStream quite some time to add support for transactions.

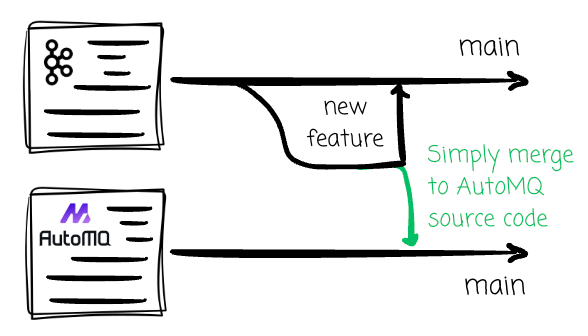

AutoMQ doesn’t think that’s a good idea.

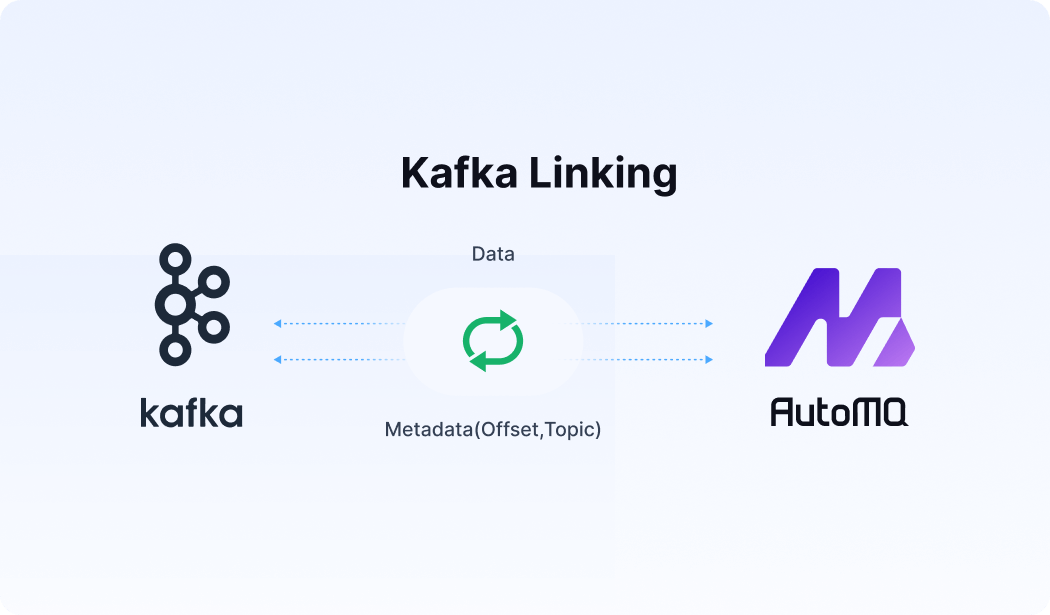

AutoMQ reuses all the logic except for the storage layer. They spent a considerable amount of time designing the new storage engine for Kafka, which can work smoothly with object storage while still providing the required abstraction for the Kafka protocol to function with.

By doing this, AutoMQ can confidently offer 100% Kafka compatibility for its diskless offer; if Kafka introduces new features (such as queues), AutoMQ can seamlessly integrate them into its source code.

Another notable feature is that AutoMQ offers an open-source version, enabling you to experiment with it or self-deploy it on your own. Currently, it is the only open-source, production-ready, diskless Kafka solution on the market. All other ready-to-use solutions are closed, and the KIP: Diskless Topic is still under discussion.

Don’t sacrifice the latency.

Writing to object storage is surely slower than writing to disk. Some diskless offers choose to sacrifice low-latency performance; they wait until the message persists in the object storage before sending the acknowledgment message to the producer.

This trade-off, however, has serious implications. When latency degrades (by orders of magnitude), clients often need to spend additional time re-tuning configurations, from concurrency levels to cache sizes (more on cache later). In critical, latency-sensitive scenarios such as finance, this level of performance degradation is often unacceptable.

AutoMQ doesn’t want to do that.

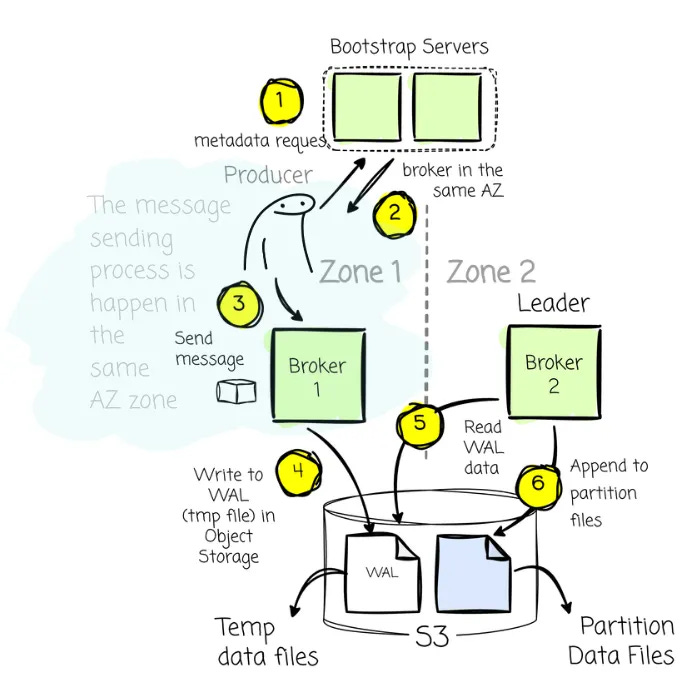

They leverage the classic idea from the database world for this purpose: the Write Ahead Log (WAL). It is an append-only log structure for crash and transaction recovery. The principle is simple: all data changes must be recorded in the log before they are applied to the database’s data files.

By following this rule, if the system crashes after a transaction has committed but before its changes are written to the data files, the system can use the WAL to reapply these changes. This is important for the DBMS to ensure durability.

Back to AutoMQ, every broker will have a WAL, which is essentially disk services such as AWS FSx or an equivalent service from other cloud vendors. By relying on these robust, shared services, which are often replicated across AZs, AutoMQ ensures it can handle AZ-level failures.

Upon receiving a message, the broker writes it to the memory buffer and returns the ack response to the producer only after it persists in the WAL. By doing this, the client doesn’t need to wait for messages to be written to object storage, thus significantly reducing the latency.

The messages are batched and asynchronously flushed to object storage later.

Sending an ack response right after the message is persisted in the WAL (disk) is indeed faster than waiting for the batch of messages to be written to object storage. A quick note is that since the disk device serves mainly as a WAL to ensure message durability, the system only needs a small amount of disk space. The default AutoMQ’s WAL size is set to 10GB.

Leader-based vs the leaderless

At its heart, Apache Kafka is a Leader-Based system. For every partition of a topic, it will typically have a single leader and zero or more followers. All writes must go to the partition’s leader, and reads can be served by a leader or the partition’s followers. AutoMQ still goes in this direction.

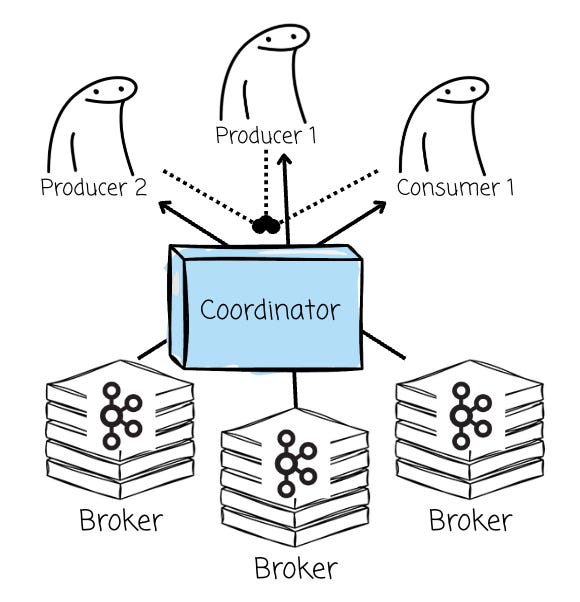

In the diskless architecture, since all brokers now share the object storage, some vendors, such as Bufstream or WarpStream, believe that a leader-based architecture is no longer necessary. Instead, they treat all brokers as a homogeneous, stateless compute pool; any broker can accept a write for any partition. This is usually referred to as leaderless architecture.

In this section, we will explore various aspects to understand the trade-offs between these two architectures.

Extra component

For the leaderless architecture to work, the deployment must have an extra component compared to the original Kafka solution. As every broker can serve read and write operations, the Coordinator must present to assign a broker for the read/write clients, manage metadata, and re-implement all of Kafka’s advanced features that the partition leader previously handled.

This reliance on an external coordinator, however, introduces some side effects. It complicates the write path by adding dependencies beyond the broker itself. It also increases the cost of maintaining Kafka API compatibility, since core Kafka features (such as transactions or idempotent producers) must be fully re-implemented with the involvement of the coordinator.

AutoMQ’s leader-based approach doesn’t require a Coordinator, as the message-producing/consuming mechanisms still resemble Kafka. Clients will issue metadata requests to the bootstrap brokers to identify brokers, their availability zones (AZs), and topic partition leaders. When producing data, the client always attempts to communicate with the leader of a given topic partition. On the reading side, the client may connect to the leader or one of the replicas.

The leader concepts are still present in AutoMQ, so no additional components are needed.

Write flexibility

Leaderless provides the flexibility for writers.

One of the benefits is to reduce the cost of cross-availability-zone (cross-AZ) transfers significantly. The system can seamlessly route traffic from a producer to the broker located in the same zone as the producer, preventing the incurring of cross-AZ costs.

The AutoMQ’s leader-based architecture can easily eliminate cross-AZ traffic on the write side by leveraging the shared object storage. There are two scenarios here:

If the leader is in the same zone as the producer: great, ideal case, the producer sends messages to this broker as usual.

If the leader is in a different zone: when the producer asks for the broker information to send messages; instead of returning the info of the leader (which is located in a different zone), the discovery service will return the broker that is in the same zone as the producer.

- This broker writes messages from the producer into the temp files object storage. The leader will later pick up these temp files and write the data to the actual partition location. This is because, in leader-based architecture, all writes to partitions must be handled by the leader.

By doing this, AutoMQ can eliminate cross-AZ traffic fees without sacrificing Kafka compatibility (leaders still write the partition data).

Data locality for reads

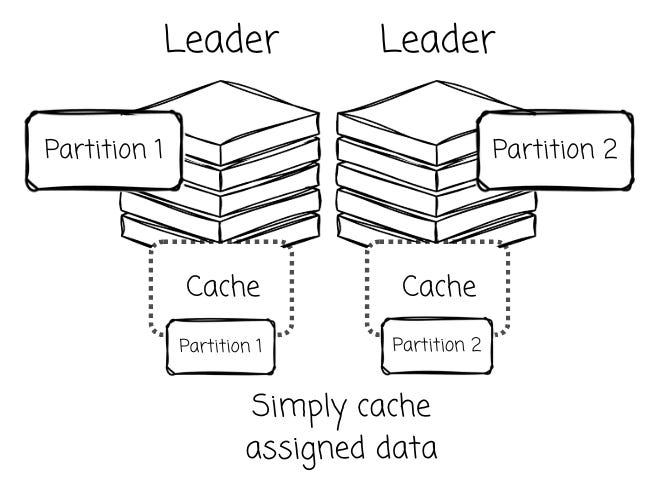

In a leader-based system like AutoMQ, the partition leader has a distinct advantage: high data locality . Since it handles all writes for its partitions, the most recent and frequently accessed data (hot data) can be cached in its local memory.

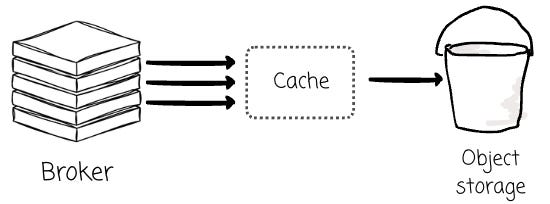

Speaking about cache, it is an essential mechanism in diskless architecture, as reading data from the object storage is not as performant as reading data from a local disk.

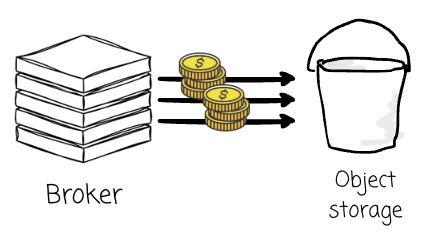

Besides the performance, issuing too many read requests will incur additional costs, as the cloud service charges based on the GET requests to the object storage. The cache mechanism could help in both performance and cost efficiency here.

This helps improve read performance and maximizes the efficiency of batching data before uploading it to object storage. AutoMQ’s design with a dedicated Log Cache for writes and hot reads, and a Block Cache for historical data, is a direct result of this architectural benefit.

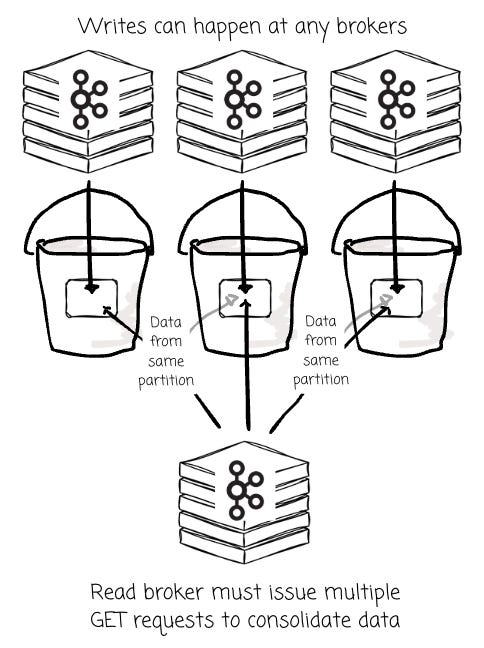

Conversely, leaderless architectures might suffer from low data locality . When any broker can write data for a partition at any time, the data for that single partition becomes fragmented across many small objects in S3, created by different brokers.

Although these objects are consolidated at the end, the broker still needs to issue multiple GET requests initially to read the scattered objects and serve the consumers. Cache surely helps here. The question is how to cache the data, as all the brokers can serve the read operations in the leaderless architecture.

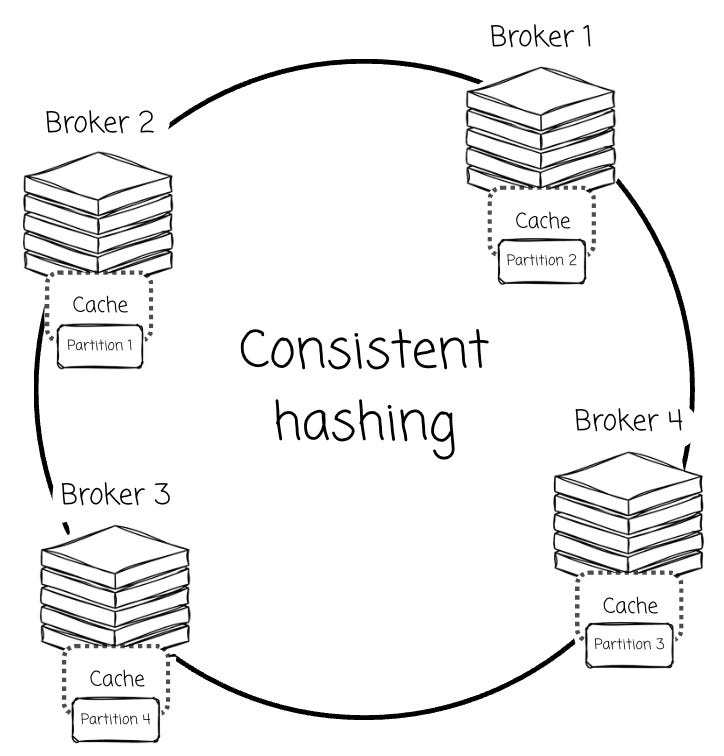

As I understand, vendors attempt to assign partitions to specific brokers. For example, Warpstream leverages consistent hashing to assign partitions to a broker. This broker is responsible for caching and serving all the data for the designated partitions.

This approach effectively falls back to the idea of a leader-based architecture , but in doing so, it introduces more complexity . To compensate for the performance and cost issues of having no local data, solutions must be engineered to work around the high latency and API costs (like S3 GET requests) of object storage.

For instance, WarpStream’s own blog explains their use of mmap as a way to minimize S3 API costs. This is thesolution to mitigate the penalties of a design that cannot perform true data locality.

Metadata management

The architectural divergence between leader-based and leaderless architectures extends deep into how they manage metadata. In AutoMQ’s leader-based model, metadata management is simple because it leverages Kafka’s partition logic.

When AutoMQ writes data, it does so directly to an already open partition, mirroring Kafka’s own process. This makes metadata storage and organization straightforward. The metadata footprint is relatively small, primarily tracking the mapping of partitions to their leader brokers and the locations of data objects in S3.

This metadata is efficiently managed by Kafka’s own KRaft protocol, which is integrated directly into the brokers. The size of the metadata is independent of the number of message batches, avoiding bloat.

Leaderless systems, by contrast, face some challenges. As they remove the concept of message partition, they must expend significant effort and write more code to re-implement Kafka’s core functionality from scratch.

Because they lack a single authority for a partition’s log, they must store detailed metadata for every single batch of messages, including its offset, timestamp, and the number of partitions it contains.

This complexity is twofold.

First, the large volume of metadata often requires a separate transactional database for its management, adding significant operational overhead and another potential point of failure to the system.

Second, it complicates the data path. The data stored in S3 is not “complete” on its own; for a consumer to read it, it must be merged with the corresponding metadata in the database.

This merging process is more complex than in AutoMQ or traditional Kafka, as a direct consequence of abandoning the simple and effective partition logic that underpins the Kafka protocol.

Outro

In this article, we first examine the challenges of Kafka in the cloud era, the motivation behind the diskless architecture, and what this architecture entails. Next, we move on to AutoMQ, the only vendor on the market that offers an open-source diskless option.

We finally explore the differences between the two main approaches in diskless systems: leader-based and leaderless architecture, in terms of extra components required, write flexibility, data locality for reads, and metadata management.

.png)